Susan Tomory

F A M I L Y H I S T O R Y

as the base of our national history

Imre Horváth’s life work

The most elevated and sacred documents of family histories are preserved on the tomb-stones and the uniquely carved wooden grave-markers of our Hungarian cemeteries. Prof. Imre Horváth, teacher and artist in Debrecen is the reviver of this silent, yet eloquent world; he made our ancestors’ world accessible to us through decades of dedicated work. He planned to place this album of collected works onto the nation’s table as a celebration of the 1100 years of the statehood of Hungary, which also coincides with the date of the new millennium. But his gift to the nation was not accepted by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences, which still continues the anti-Hungarian policies developed during the terror regime of the Habsburg age. The Academy sent his life-work back to him. It is this story that Imre Horváth tells us in his poem:

A CALL TO THE BIER

In the county of Hajdu-Bihar

I surveyed all the cemeteries;

The two and a half thousand headstones

All have been cast to the dump.

Who dared to destroy the ancestors

And their sorrows not their own?

How did they dare to silence them,

And not take on their woes?

Deceitfully they hid

Behind false experts

And stabbed the author in the back.

But their dagger fell into dust

I hope.

(The words ’they’ and ’their’ refer to the anti-Magyar Hungarian Academy of Sciences.)

How does anyone dare to slap the face of an entire country’s inhabitants by not taking into consideration their innermost, personal feelings?

Who are the ones here who place themselves in the position of judge and jury even over the dead?

What kind of power works in a place where the roots are cut?

Whose country do the people build who are jealous even of the memories of a people?

Why can’t an entire country embrace an album which contains its own cultural heritage?

Why is it necessary to destroy the country’s, nay even Europe’s largest unified reservation of ancient carved wooden grave-markers?

WHO IS RESPONSIBLE FOR THIS?

*

Imre Horváth

THE HISTORY OF THIS RESEARCH

It is close to two decades since I began the research of the Hajdu-Bihar county’s headstones[1] and this work still continues.

The goal of this research was the preservation of ancient wooden grave-markers which are disappearing at an alarming rate; this work branched out in a very short time into the research of origins too. The work started when my daughter, a college student, accepted as a school project the measuring of the Mikepércs cemetery and the preparation of its map, with which I helped her. Here I made rubbings of the inscriptions of almost every grave-marker. The awe that enveloped me at this time still lasts, because at the top of the markers I found signs and carvings, which I did not understand.

I have often been to Szatmárcseke on group outings. I have seen and heard and, by now, I have also read about the explanation of the „boat”-headstones but these explanations seemed unsatisfactory to me.

I could hardly leave these monuments and I felt a deep need to touch THEM. I capitalize this on purpose, because I felt that they were not lifeless, dead objects, but living souls, all of them. I always used the available little time on these group outings to make sketches of their beautiful forms.

These memories came to life at Mikepércs and helped the cemetery to come to life. I saw not only columns and rods, but a huge puzzle, whose key was almost in my hands and I did not know where this door would lead me. I read tirelessly, researching all the scientific studies and articles on this subject that I could lay my hands on, beginning from the turn of the century[2]. I had the feeling that I experienced the joy of these scholars when they made some important discovery in the field, from György Domanivszky to Iván Balassa. In the meanwhile, I visited the towns around Mikepércs. This is how I spent my first year and it was then that I reached the decision that I would finish this work, no matter how long it would take.

Several other people also encouraged me to continue. Dr. Dezső Baróti, a professor at Szeged University, enthusiastically encouraged me and also reminded me that all scientific work has to begin with the collection of accurate data. Slowly, my methodology evolved and I discovered the necessary tools for this work. (A checkered notebook, a pencil, an eraser and a camera.) I walked the cemeteries for over a decade on every day off, prepared the drawings and made notes.

Some of the cemeteries were hard to find, especially the old ones, where cement structures have not yet taken over the field. I walked the old paths, searched the lanes and the bushes where the really old memorials were hiding and made notes and drawings of everything that caught my attention. As an art professor, I was very aware of the fact that these drawings should not be an art project, but accurate drawings of objects that could be reconstructed based upon these drawings. It was for this reason that I prepared my drawings very accurately, measuring the engravings and profiles. Three or four such representations of a given territory already convey a feeling of the general appearance of the cemetery. In my representations, I gave special attention to the ones that were different or strange, the ones that „talked”, or the ones that the literature had already mentioned. This, of course, also required intuition. If the memory of the form is lost, the whole effort becomes futile. This realization drove me, because I was aware of the fact that, even though these grave-markers are still in place, there is no further desire for them, the need is reduced by poverty, or the fashions have changed. I heard a young woman tell an older lady: „Don’t tell me that you want to put up a carved wooden headstone for Papa, he really deserves a decent one!” This is a glaring example of distorted taste, the mentality of the new „minute men”, people who discard traditions.

I also discovered that if I was there on the field, I had to preserve the carvings and texts too. These I prepared, representing proportions, lines and character; the texts contained the meaning, but not necessary verbatim. To preserve authenticity, I made photographs of these for the purpose of identification.

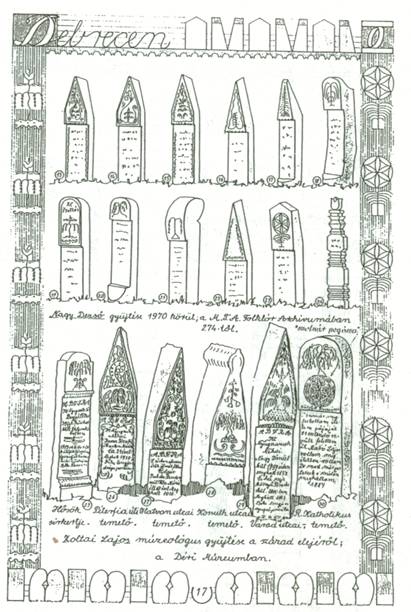

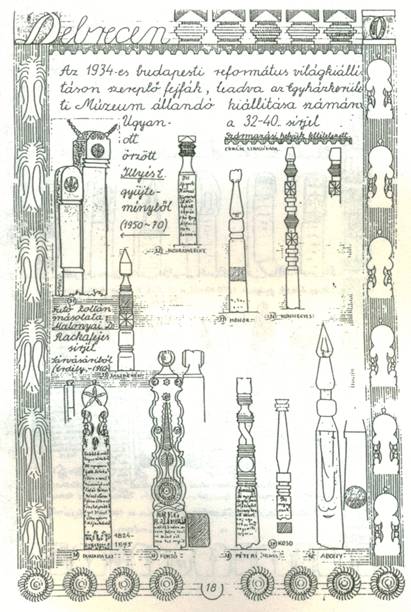

Step-by-step the material began to accumulate and by then I had to be sure that I avoided the trap of making this research a self-serving project. I began to construct the drawings in 1:10 proportion based on the initial drawings. The sketches were transferred onto 15x20 cm. drafting paper with India-ink and the wooden grave-markers were painted in a light brown watercolor. I also prepared a title for each page.

I had already finished several hundred such pages when Professor Dr. István Kiszely came to give a lecture at my workplace, the Ybl Miklós Műszaki Főiskola (Miklós Ybl Technical University) about his expedition in Central Asia. At this time, I showed him these drawings and he encouraged me and said an album should be made of these collected drawings.

Therefore, I copied the material onto A2 pages. Title pages, decorative borders and the whole community’s comprehensive picture, including a short description, accompanied these pages.

In each settlement, I drafted the place of the cemetery onto a map with the year of the research. The number of residents was also added according to the 1941-1991 official statistics. I did not strive to give a comprehensive history; my goal was to show the headstones. Since I was teaching architectural graphics, it was natural for me to give a feeling of the topography and the environment surrounding the grave-markers, to bring their image to life, thus avoiding a dry, lifeless look in the drawings. A 3 cm. wide border surrounding the markers was used in the following way: on the top and bottom part of the border I drew plastic art, on the two sides I placed representative flower motifs; this is how the appearance of the pages evolved and this method was continued throughout the album.

In time, I visited all the Hajdu-Bihar settlements and finally came to the end of the measurements. Now the organization of the already collected material awaited me, which I was able to do at home. It was in the early days of my project that a sentence of Ákos Koczog, an earlier researcher caught my attention. He pointed out that the dove images at the top of the grave-markers originated from the old pagan religion. The Catholic Church only tolerated them at first but later assimilated them. – I also found an article in an old edition of the Ethnography from the 1930’s concerning the carved door-columns. It showed a great number of birds of all kinds, not only doves, which were standing, sitting or reaching high, in many different positions. It seemed natural that I found, east of Debrecen, at a distance of about a day’s journey, the territory of these „bird ornaments” of which Koczog wrote.

After this discovery, I saw these old carved wooden headstones in a different perspective. I realized that they were decorated purposefully with ram-horn designs, with the requisites of snake, horn and horse designs. By then, I was convinced that I was in the world of the 9th century designs and totem poles.

This realization became the governing principle in my method of organization. I tried to find the connection between the headstones according to the top designs, flower motifs, the use of space, and abstractions within all these.

It is understandable that these totem-poles must have survived the forced Roman Christianization process throughout the centuries and that these were not the „inventions” of Protestanism.

Since the basis of this organizational process was the finding of the evolution of forms, noting the variations, some plastic forms – totems – and the territories that contained them became more and more evident. I tried to summarize these in the chapter on topography. It became clear that these totem-designs had one epicentrum where the forms were clear and readable, with peripheries where the designs became slowly distorted and finally disappeared, giving way to the new designs of the neighboring territory. Of course there are several overlaps in design, according to the historical layers.

I made an attempt to show the possible connection between the different ethnic communities and the designs.

I collected in a separate chapter the orientation of the headstones and graves.

The inscription (name, birth and the date of death) can be seen on most of the grave-markers. So I was also able to prepare statistics of the data concerning the deceased, according to settlements, and I gave each a number for identification purposes so that relatives can easily find the graves of their loved ones.

In the meanwhile „Földrajzi nevek etimológiai szótára” (The dictionary of Etymology of Geographical names) was published and I was able to collect data concerning the origin of a given town or settlement. I was able to add to this knowledge the plastic appearance of the headstones. I tried to draw attention to the archaeology and totem-cult of these people too. The orientation of these graves and headstones may be of help to the future research of the applied sciences.

The drawings of the grave-markers are exact; everything else is sketchy but correct. I accomplished my goal but the end result became far more significant than the original plans.

I achieved the full documentation not only of Hungary’s, but of Europe’s greatest and oldest unified territory of grave-markers with all its implications. The family, clan and tribal connections became visible and they outlined the territories of ancient settlements. I found concrete evidence, and tangible memories of the ancient Hungarian religion. The since published books of Adorján Magyar and Dr. Tibor Baráth in the field of ethnography and ancient history will shed even more light upon these ancient structures and our Magyar cultural heritage.

*

Prof. Imre Horváth’s masterpiece was refused by the Hungarian Academy of Sciences (MTA), which was founded by Count István Széchenyi in the 19th century, with the goal of saving Hungarian cultural treasures. The Academy refused to accept this very important work. Presently, the author and the Journal of Hungarian Studies are looking for contributors toward the publishing of this masterpiece.... The publishing of this book will not only be of immense value in the preservation of Hungarian cultural heritage, but it also adds to the further understanding of European culture.

*

(This article was published in the 11th issue of the Journal of Hungarian Studies in 2000 Despite our efforts no contributions were offered toward the publication of this work.)