Bibliography

Brace, Charles Loring. 1852. Hungary in 1851.

New York: Charles Scribner.

Gracza, Gyorgy. 1894. Az 1848–49. i Magyar Szabadságharcz Története.

Budapest: Lampel Róbert (Wodianer F. és Fiai) Kiadása.

Ives, C. Margaret. 1979. Enlightenment and National Revival.

London: University of London.

Nagy, Geza. 1900. A magyar viseletek tortenete. Budapest:

Franklin-tarsulat.

Szabad, Gyorgy. 1977. Hungarian Political Trends between the

Revolution and the Compromise (1849–1867). Budapest: Akademiai Kiado.

Monorne Rohlik, Erzsebet. 1990. A varazsereju himes tojas. s.n.:

Neutron kiado.

| Award for Hungarian

American The Hungarian Association awards the Arpad gold medal for disseminating knowledge about Hungarian embroidery and Hungarian history, especially the 1956 revolution, in the United States. On November 29, 2003, at the annual meeting of the Hungarian Congress, Eniko Farkas was the recipient. In 2002, she was honored with the Educators Award of Excellence, given by the Embroidery Guild of America. |

Eniko Farkas

(edf2@cornell.edu)

is a Hungarian community scholar and independent researcher whose interests include textiles and the needlework and food culture heritage of immigrant women. She teaches Hungarian embroidery for the Embroidery Guild of America and is a board member of the New York Folklore Society. An expanded version of this article was originally presented before the Silenced Voices Panel at the annual meeting of the American Folklore Society, Rochester, on October 19, 2002.

New York Folklore Society

P.O. Box 764

Schenectady, NY 12301

518/346-7008

Fax 518/346-6617

nyfs@nyfolklore.org

There are many ways to communicate without words—and there always have been. In tribal cultures, for example, war paints indicate coming action. A sophisticated system of using flowers to send coded messages, practiced in late antique and medieval times, enjoyed a revival in the early nineteenth century, when bouquets expressing the “language of flowers” communicated lovers’ intent.

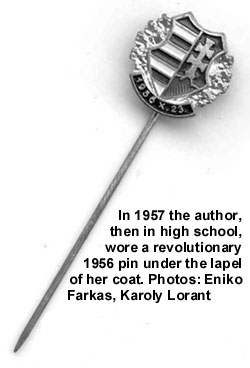

Episodes from my own life inspired me to become interested in finding out how people have used coded messages to resist political oppression and injustice. In 1956 I was a young factory worker in Hungary, without hope of getting a high school education. When the Hungarians rose up against communism in 1956, I was an eyewitness. I saw people fighting and dying on the streets and heard about the cruel deaths of friends. I became a passionate supporter of the uprising, and my spirit was crushed when it failed. I collected revolutionary pins and newspapers and leaflets published during the uprising, even though I knew that the communist Hungarian government, with the approval of the Soviets, sought revenge on revolutionary participants and supporters. Some people were executed for the slightest offense; others were jailed, tortured, or harassed. We all heard the stories through the grapevine, usually at open-air markets where women could talk to each other about these things. The resistance had to be carried on in secret, silently.

|

My sixteenth birthday was

approaching when in spring 1957 I applied for the second time to

the most prestigious high school in Hungary, the Geologist

Technician High School. To my surprise I was accepted. Being two

years older than my classmates and a former laborer, I fit in

poorly. But for the first time since I was ten years old I had a

winter coat, bought with the money we obtained from selling my

aunt’s furniture when she left for the West. To keep my soul

alive, I wore my revolutionary pins under the coat’s lapel. Because I didn’t join the Youth Communist Party—I loathed communism—I was suspected of being a revisionist by the school principal, a stalwart communist. One day, while I was in class, the Youth Communist Party kids searched my coat for evidence and found a revolutionary pin under the collar. When I noticed it was missing, at first I thought I had lost it. But after my third and last pin disappeared, one of my classmates told me what was going on. Now I would not be accepted as a party member or allowed to work in Budapest. My silent resistance had ruined my chances of going to college, because being a party member was a prerequisite for admittance. |

I was not the only person in Hungary quietly standing up for the 1956 revolution. Molnar Adrienne, of the 1956 Research Institute, told me that the widow of an executed revolutionary wore black to mourn her husband and was warned by the Communist Party secretary not to “demonstrate your pro-56 sentiments with your black dress.” Yet both men and women wore black arm bands to show support for jailed people.

School officials were sensitive to the use of dress to express dissent. After my aunt emigrated to the United States, she sent us packages of used clothing, including the castoffs of Cornell students. In my last year of high school, in 1961, she sent me red felt shoes and black stockings, and one morning I decided to wear these fashionable American clothes to school. Unbeknownst to me, Patrice Lumumba, the communist prime minister of the Congo, had been assassinated the night before. When I showed up in my finery, the school principal thought I was mocking Lumumba’s death. I was threatened with expulsion but was able to convince a teacher that I had not heard about Lumumba’s death, and I was given a reprieve: I would be allowed to graduate, but I was an undesirable character who could never go to college or get a job in Budapest. My dreams of a college education went unfulfilled until I graduated from Cornell University, forty years after the uprising.

Historical Precedents

Beginning with those personal recollections, I decided to look at how Hungarians, women in particular, have expressed their political sentiments in textiles. One example involves Hungary’s subjugation by the Austrian Habsburgs, which began in the sixteenth century. The Austrian domination was not well accepted, but since armed rebellion had failed, the aristocracy had few ways to show its displeasure. When Joseph II became the ruler of Austria and Hungary in the late eighteenth century, he insulted Hungarians by refusing to be crowned with the Hungarian crown; hence his nickname, “the king with the hat.”

| His

anti-Hungarian stance inspired a nationalistic cultural revival,

and it became a form of resistance to appear at aristocratic

social gatherings wearing “Hungarian” dress, in protest against

the Austrian court fashion. The style consisted of a bodice, a

lace shirt, a lace apron, an embroidered skirt, and a headpiece. The Austrian government prevented Hungary from developing its own industries, thereby keeping its economy based on agriculture. In the 1840s there was an attempt to create a Hungarian textile industry, which the women of the Hungarian nobility and middle class patronized by wearing dresses from domestic textiles. This fabric was blue and decorated with white dots. Many countesses wore dresses made out of this fabric to charity balls, with rosette lapel pins made from the national colors. |

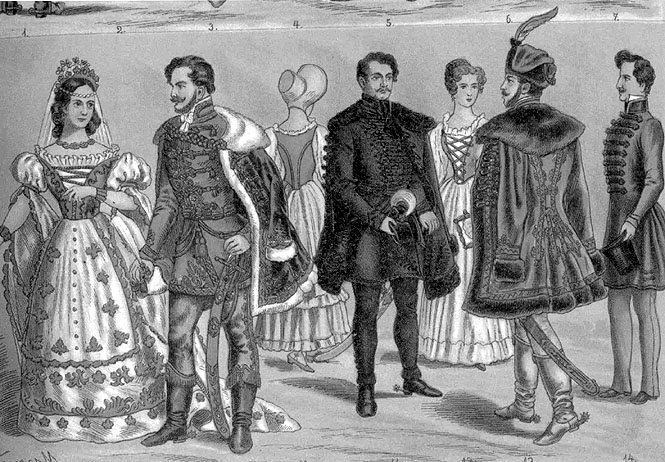

The fashions of seventeenth-century Hungarian noblewomen were the model for a national dress worn two centuries later. Source: Merenyi, Lajos, Herceg Eszterhazy Pal (Budapest: A Magyar Tortenelmi Tarsulat Kiadasa, 1895). Below: Hungarian women of the early nineteenth century adopted the historical fashion to express their nationalism. Source: Nagy, Geza, A Magyar Viseletek Tortenete (Budapest: Franklin-tarsulat, 1900). |

|

|

In March 1848, Hungarians revolted against the Habsburg monarchy. When the emperor accepted some of their demands, Hungarian men celebrated by wearing swords and the Hungarian tricolor emblem on their hats, in red, white, and green. The women wore tricolor bonnets, and unmarried girls put on beaded headdresses, or pártas. The revolution was soon crushed, however, with the help of the Russian czar. An American traveler, Charles Loring Brace, founder of the Children’s Aid Society, observed in his book Hungary in 1851 that the Austrians took revenge by forbidding the wearing of the Hungarian costume; a young boy was imprisoned for wearing a Hungarian blue jacket with embroidery and an embroidered cap. Even though the display of the Hungarian colors was forbidden, some ladies, Brace reported, managed to get them into their clothing, and others wore black dresses as a sign of mourning for their country.

Resistance was also expressed in jewelry. After a noblewoman whose tenants had burned an effigy of Franz Joseph, the Austrian emperor, was beaten with broomsticks by 350 soldiers, all over Hungary pieces of broom were put into gold settings and were worn by ladies as pins. Women also wore heavy iron bracelets that imitated handcuffs in remembrance of the Hungarian prisoners kept in the jails of Arad and Temesvar; some of these bracelets were engraved with the initials of the thirteen generals and politicians executed at Arad in 1850, and the letters spelled out in Latin a sentence mourning the executions. A woman recently told me of seeing such a bracelet, a segment of which had a depiction of a skull, among her family’s possessions. Once the Austrian authorities came to understand the meaning of these bracelets, their wearing became a punishable offense.

|

After the fall of the Hungarian government in 1848, women wore kerchiefs made from a domestic textile of a particular design to show that they mourned its leader, Louis Kossuth. This example is in the Paloc Neprajzi Magangyujtemeny (Paloc Private Folklore Collection), in Matrafured, Hungary. Photo: Eniko Farkas |

Passive resistance took many forms. Women sewed into clothes mementoes of the revolution—a piece of the flag, a badge. Women wore necklaces and bracelets made from coins minted during the years of the revolution. Actresses carried bouquets in the national colors when appearing on stage.

An interesting example of resistance is how the women of Nograd flouted a law that forbade mourning for Louis Kossuth, the head of the fallen Hungarian government (whose wife was noted for her wearing of the national blue-and-white fabric, called the honi). The 1848 money printed by the free Hungarian government was called the Kossuth banko, and it became the beloved and cherished memento and symbol of the revolution. Possession of such notes was severely punished. The women of Tard, in northern Hungary, embroidered the red-and-black pattern of the Kossuth banko into their cross-stitch work and wore dresses made from this fabric. In the Paloc region, the women wore a certain type of blue-dyed kerchief to show mourning for Kossuth. In the village of Csernaton in Transylvania, even Easter eggs were decorated in patterns that signified mourning for the failed revolution.

More recent examples of silent political resistance include the use of national colors in household decorations and folk arts by the Transylvanian Hungarians after the First World War. Transylvania, which had been part of Hungary, was given to Romania by the victorious allies. To rebel against the Romanian oppression of Hungarian culture, Transylvanian Hungarians altered the decoration of household and folk art items. Women started to integrate the national colors into textiles, and Transylvanian bead necklaces and bead-decorated items were made in the Hungarian national colors, some with the Hungarian coat of arms.

Strong political sentiments can be disguised in coded decorations, in hidden objects, and in textiles imbued with meaning. This “silent” resistance can be heard, of course, as I discovered when my classmates found my tokens of rebellion against the crushing of the Hungarian uprising, and governments eventually catch on and punish the offender. In my case I was denied the opportunity to go to college. But ultimately, the government did not prevail against me.

"Political Resistance in Hungarian Dress" by Eniko Farkas appeared in Voices Vol. 30, Spring-Summer 2004. Voices is the membership magazine of the New York Folklore Society. To become a subscriber, join the New York Folklore Society now.

HOME |

ABOUT NYFS |

PROGRAMS & SERVICES

| PUBLICATIONS |

RESOURCES

| CALENDAR |

WHAT’S FOLKLORE?

| MEMBERSHIP |

GALLERY |

SHOP |

SEARCH |

CONTACT US

© 2006, 2005, 2004 New York Folklore Society